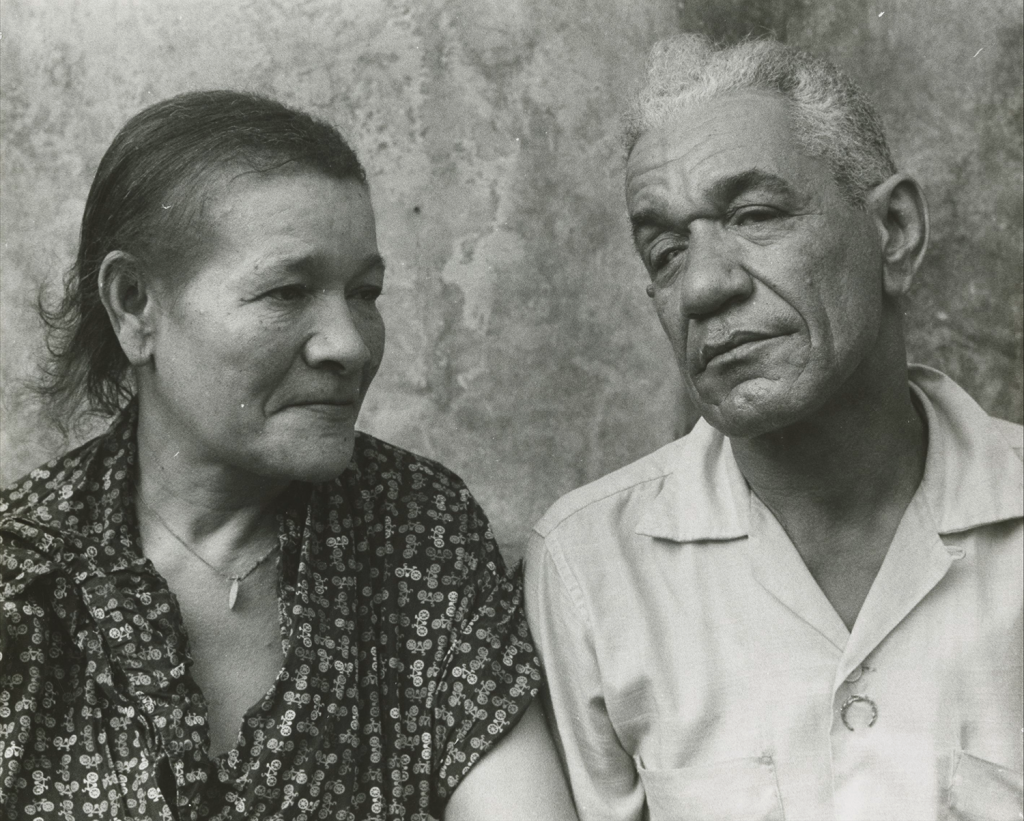

Billie and DeDe Pierce at their home at 1619 N. Galvez, Ralston Crawford Collection, 21494. All images courtesy of Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans.

Introduction

Melissa A. Weber

Over the years I’ve often heard musicians describe music as being as much about what you don’t play as what you do play. Similarly, historiography is as much about what is left out as the stories we tell. This is particularly the case when it comes to origin stories and the roles they play in defining what something is and will be.

The Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, a division of Tulane University Special Collections (TUSC), represents New Orleans music and culture since the late nineteenth century. Archival collections consist of primary-source materials, such as photographs and oral histories. The artists and stories included in this archive help tell the not-so-neat origins and development of musical cultures of New Orleans, including jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, and Black American popular music.

Featured here are selected looks and listens of stories and storytellers, some of whose perspectives have been left out of histories of popular American music, but whose voices are foundational. To tell this story, I’ve utilized portions of two of the Hogan Archive’s most requested collections, the Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography and the Hogan Archive Oral History Collection.

The Hogan Archive was first established in 1958 with the oral-history collection, as Ford Foundation funding allowed for an oral-history fieldwork project, initiated by Tulane University graduate student Richard “Dick” Allen, to record stories of music makers in New Orleans. The photography collection includes over seven hundred images captured by visual artist and photographer Ralston Crawford, who visited New Orleans and documented its music, architecture, and moments of celebration and life between 1947 and 1960. The real-time development of both collections was often challenged by Jim Crow–era segregation, which made it difficult for the white Allen and Crawford to socialize with African Americans. On the other hand, collections created by documentarians of color may not have been welcome at Tulane in 1958, as the university remained segregated until court hearings in 1962 and the first Black students were admitted in 1963. The history of documentation and collecting indelibly shapes how we understand the origins of New Orleans music styles, such as jazz, but also the history of the Hogan Archive, for which I serve as its first Black American curator.

Also included with this assembly of archival materials showcasing the stories and history of New Orleans jazz and New Orleans music is a new, contemporary interview about the origins of jazz—and the term “jazz” itself—with internationally acclaimed New Orleans–based artist Nicholas Payton. Over the past decade, Payton’s writings and lectures have advocated the use of a term he coined—Black American Music, or #BAM—over the white-supremacist connotations that have been associated with the term “jazz” since its inception. New Orleans is not simply the “birthplace of jazz” but, rather, the foundation of all of American popular music culture, which comes from Black American Music.

Melissa A. Weber

Curator, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz

Tulane University Special Collections, New Orleans

February 2021

The words of Nicholas Payton as told to Melissa A. Weber

January 19, 2021

Black American Music #BAM

Well, that was a term I came up with after I wrote a piece in 2011 called “On Why Jazz Isn’t Cool Anymore.” I would say it’s an essay, but some people called it a manifesto, all kinds of different things. I’ve heard it called a poem. And it basically was comprised of me cutting and pasting [words from] me doing a live tweetstorm one afternoon in my hotel. I did not conceive of it as a piece or an original work, but, after I was finished, I saw a lot of very strong reactions, both positively and negatively, and I felt maybe I was onto something because I was actually writing about it for two years prior, about my disdain for [the word] jazz. But, for whatever reason, this afternoon, me tweeting, I felt there was a different energy in the air. So after I was done with my stream-of-consciousness tweeting, I cut, copied, and pasted each [tweet] and put it in a Word document and that is the piece that is called “On Why Jazz Isn’t Cool Anymore.”

A lot of people took it as me attacking the music, but I wasn’t, per se, even though there are elements of the music that I do vehemently object to. But by and large, I was more attacking the usage of the term jazz and jazz as a construct, as a means of controlling Black music by an oppressive white system, marginalizing its creators from their creation, and holding the lion’s share of the profits while the artists and the creators get a pittance. So I think this jazz idea is one that has not served not only the artists, but it hasn’t served the [Black] community, and it is ultimately antithetical to the whole purpose of the music.

Because, you see, when we were transported here during enslavement, one of the first things they did was force us to not speak our native languages. So we developed new means of communicating with each other through either field songs, field hollers, work songs. These things eventuated into forms like the Black gospel tradition or blues music, which are the roots of what had later become known as so-called jazz. And Congo Square is central to that because it was one of the only places, if not the only place, the enslaved Africans were given a space to practice drumming, singing rituals, and so forth. And it’s out of the energy of Congo Square, it’s out of the energy of New Orleans, that many years later produced the world’s first pop star, Louis Armstrong. Though there are those before him, like his direct mentor, King Oliver, Armstrong revolutionized Black music and was the genesis of the pop star, which is an idea that didn’t exist before him largely due to the fact that here was this young artist who had a new voice and that voice coincided with the advent of a new technological medium called the phonograph, or the record player.

The origins of jazz music

The first recorded jazz band, in reference to jazz being referred to as music, is the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, which was led by Nick LaRocca, who is a known racist in that he not only appropriated Black music and minstrelized it, but he’s also gone on record as saying as such, that he would basically try to make his version or “class up” the Negro musician, the Negro music, if you will. So yeah, he made the first jazz recording, which was by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and that name itself is problematic. One, they weren’t original. They’re not the first. Dixieland, we know that is the Confederate South, which did not want to abolish slavery. And jazz, in this context, was spelled J-A-S-S, which is said to be a contraction of jackass. And the first record they made was “Livery Stable Blues,” which was all animal and jungle sounds, which, again, [was] basically minstrelizing our serious Black music.

White people appropriated it and called it jazz, but the [Black] artists themselves did not create jazz music. In fact, Armstrong has gone on record saying that, Sidney Bechet has gone on record saying that. All these early [Black] artists did not call it jazz music. The first recorded jazz band was the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and they were racist appropriators.

Challenges or problems in documenting stories of Black American music and musicians

We don’t do it. And when it’s done, it’s not usually us doing it. It is the same structures that seek to marginalize us and keep us from our creative capital, which is a problem, and kind of antithetical to our Black—I’ll use Black and African interchangeably—traditions. Because our Black, African traditions are an oral history, passed down from master to student. But as we have increasingly become more reliant on Western methods of documentation and classification and publications and record companies, these types of systemic capitalist constructs, we’ve relied less on our natural, instinctual paths. Which I find to be intrinsically problematic, because it is these very westernized, European forms of documentation that have ultimately served to hinder and harm our expression as a people. They have not served us well, I think.

So the more we rely on their ways … this is not even being negatively critical of their ways, it’s just that it’s a different way from how we’ve done things. So it doesn’t serve our model as well as the things that are native to us. Like there are certain foods that are native to certain people who live in certain regions, and if you take that person out of that region and make them start eating things that are not native to their systems, they can very well develop diseases and sicknesses. So it’s the same idea.

Examples of the past, present, and future of Black American Music

There are countless artists: [Louis] Armstrong is the first pop star, but all the greats: [Duke] Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday. I can go on and on. Lester Young, James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, J Dilla, A Tribe Called Quest, Erykah Badu. All the great Black artists are a part of Black American Music. That’s the point. I didn’t seek to use a replacement term for that which is known as jazz. Because the whole problem to me is that it has isolated itself and has created this elitist energy that seeks to place itself above these other art forms in a way of looking down on them in some kind of way, or seeks to isolate itself completely from these other forms. Which to me, if we look at it like a tree, that’s like the roots being separated from the trunk and the branches. Well, then the whole tree dies, because it is not connected to the source.

So because hip-hop and R&B and soul and trap do not recognize themselves as being part of so-called jazz, then these art forms suffer because they don’t think someone like Lester Young has anything to do with them. They don’t think someone like Marvin Gaye has anything to do with them. Even though these are the children of Marvin Gaye, even though Marvin Gaye is a child of Charlie Parker and Lester Young. So this is the more communal type of aesthetic, a Black, African aesthetic of a continuum, as opposed to things being genre classified and looking as if they have been created in a vacuum.

So it is a continuum. And I think it’s important for us to understand that, otherwise you may waste decades rewriting history that you already have access to. The elders have already done the work. Why not use that as a springboard and a starting point and go from there, if the work has been done? So the less connected you are to your past, at best, you may wind up redoing things that have already been foundationally laid out for you. At worst, you may wind up working against decades and centuries of traditions that exist. That’s not to say traditions aren’t meant to be re-evaluated or even broken. However, you need to earn the right to break these traditions and you can’t earn that right unless you first know what they are. And I feel like that’s a bigger problem with each successive generation.

And again, another offshoot from this very binary, Western way of thinking that many Africans have adopted is that we don’t want to credit our predecessors. I recently saw an interview of some young hip-hop artist, bragging almost, that he couldn’t name two Andre 3000 songs. Like, how is that something to be touting? You should actually be ashamed of yourself. These were big hits, and you were ten years old at the time. Actually, I don’t believe that you don’t know these songs. There’s no way you don’t know “Hey Ya!” and you were ten years old when that album came out. But we’ve fostered and nurtured this culture that celebrates the youth at the expense of tradition and the elders, and I find that to be deeply problematic. And it actually signifies the death of Black culture. Again, it’s cutting the roots off from the rest of the tree. The tree dies. You can do it. I just don’t think it’s wise if you wish to have a healthy tree.

The role of New Orleans in American popular music culture

I mentioned Congo Square and a lot of the early New Orleans musicians, but New Orleans has had its hand in American popular music the whole time. It didn’t start and end with Armstrong and Bechet. Fats Domino is said to have made the first rock-and-roll album. Drummer Earl Palmer is said to have played the first rock beat; he was a New Orleans drummer. Then we have a group like The Meters, who were very instrumental in the development of the funk style of the late 1960s, early ‘70s. Then we have the resurgence of artists adopting a more straight-ahead aesthetic, like Wynton and Branford Marsalis, the Marsalis brothers; the Jordan family, like Kidd Jordan; Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, then later Harry Connick, Jr. And these are also families.

So the Marsalises, their father, Ellis Marsalis, was very instrumental with Harold Battiste in the ’60s with AFO (Records), and Harold produced, like Dave Bartholomew did with Fats Domino. Harold produced a lot of early R&B hits like Barbara George’s “I Know.” They worked with Tami Lynn, had the AFO Compendium, which was one of the first conglomerates of Black artists composing, recording their own music, owning their own masters, owning their own publishing—or Harold was, at least, anyway. Then we have even in the ‘90s with bounce and hip hop, the Hot Boys, Cash Money (Records), Master P. We have Lil‘ Wayne, Baby, all these artists.

And then on up again through people like myself. And then after me, people like Christian Scott. So New Orleans has had a hand in the new advents of Black American Music in different forms from the inception of recorded music, at the beginning of the century, to today.

Creating Music During the Pandemic

The process of being an artist, of being a creative, doesn’t really change. The things that are going on around me may change somewhat, but the place where I derive inspiration and my process doesn’t tend to change that much. The instruments may change. The sound may change a little bit. But the space and the sources from which I pull from are still the same. I may have potentially released the first quarantine album, which was kind of a spoof on my previous album, Relaxin’ with Nick, on May 27, 2020. I released Quarantined with Nick and it addressed all the things that were happening, foreshadowed even some of the things that were going to happen with regard to this pandemic, the likes of which we haven’t seen in a hundred years.

So basically everybody who’s going through it, most of us have never lived through this experience before, but I didn’t stay there. The next album was Maestro Rhythm King. So, I released two albums in 2020. Quarantined with Nick sort of feels—at least initially, in the sequence of the album—like it starts off with an angst, a bit unsettled, and that’s because that’s how the beginning of the lockdown was. It was almost like we were blindsided. And then the album starts to warm up a little bit around a ballad I wrote for COVID called “Tenderona.” And then it gets a little bit more soulful. As we settle in, the album settles in. But Maestro Rhythm King is kind of on the other side of that. Like, it’s a very warm, lush, old-school R&B album, if you will. And the title is derived from the drum machine that I featured on the album, the Maestro Rhythm King, which was used heavily by Sly Stone in one of my favorite albums, There’s a Riot Goin’ On. I played all the instruments and also sang on that album, but it’s very different from Quarantined with Nick.

And I have several other irons in the fire. I’ve been working on another album, with the gentleman who used to be a side man in my band, Marcus Gilmore, the drummer and grandson of the great Roy Haynes, who was himself a master drummer. And we’ve been working in collaboration with Kwame Brathwaite’s son, Kwame S. Brathwaite, and a friend of ours, Brandon Baker. And … Marcus and I have been co-composing a piece of music to go with the photographic works of Kwame Brathwaite, [who] was very instrumental in a part of the “Black Is Beautiful” movement of the ’60s. So, they would have these models, the Grandassa models, who were among the first Black models to be featured in print ads with Afro hair, dark skin. Basically, ads celebrating the features for which we were made to be ashamed of for hundreds of years. A lot of Brathwaite’s photos are centered around Black beauty, Black power, or Pan-Africanism, which was a strong ethic edict of the “Black Is Beautiful” movement. We’re in a similar moment right now. So it’s quite timely that we’re working on this project again, celebrating foundational Black ideals.

Reactions to Payton’s Writings and Discussions about Black American Music/#BAM

I think, initially, people didn’t know where I was coming from. So you have to look at it like whatever groundwork Max Roach or whomever may have laid, or the times Miles Davis said it in interviews and it was largely overlooked. It was almost as if no one had ever even heard of this before. And being that I was someone touted during an early part of my career as the second coming of Armstrong, it was viewed as treason that this somehow “savior of jazz music” was going against the very thing it almost seemed, in many ways, a lot of people hoped I would, specifically, perpetuate. So I think that is also an element that disturbed people deeply, not only that it was being said, but also that I was saying it. I think I was ahead of my time.

Because look at what’s going on with race relations in the world now. And everybody’s essentially saying, every day, what I was saying almost ten years ago. So I was well before Black Lives Matter. After Black Lives Matter, a lot of people who were my strongest dissenters have come to understand my position at that time, when we were at the height of the Obama era and some people even thought we were “post-race,” that this was a thing of the past, that we had finally overcome because we had a Black president. Now that seems pretty foolish. You know we just, last week, saw white supremacists storming the Capitol building.

So white supremacy is imploding, right now, in front of our very eyes. Now, the idea of Black American Music doesn’t seem as angry as it did then. Now we have Black Lives Matter, but we didn’t have that then. So, I think a lot of the misunderstanding around me was that I simply was ahead of my time, or ahead of the time for which people could understand, really grasp why I was even making that stance. Now you have universities who are thinking of changing their jazz programs to Black American Music programs. It’s a different day.

It’s been an affirmation to soldier on for this vision. Still, through all the difficulties, I remain steadfast in my feeling that jazz is a problem, that it is the musical equivalent of the “N word” for Black music, and our music is deserving of a better title than jazz. I just waited for the environment to present itself, where people could see what I meant. And I get that a lot of people may have gotten turned off by my language at times because I curse. But, you know, that’s my method. That’s my style. There are plenty of other styles used by people who do things their way. And that’s fine. I do things my way. I’m more of a Malcolm X type, if you will, than a Martin Luther King. I’m more fire and brimstone, [I’m] more of that aesthetic than congenial and mainstream—not for everybody. And that’s okay for me. I’m okay with that.

-

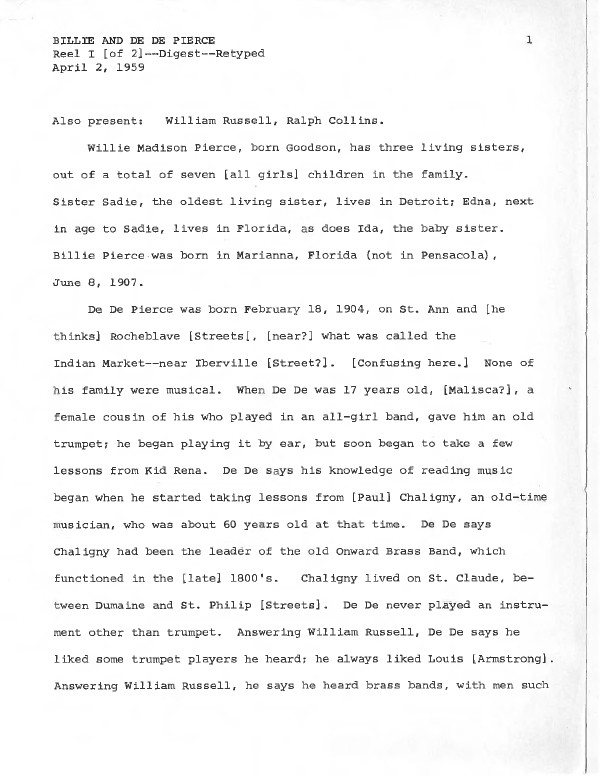

Billie and DeDe Pierce

April 2, 1959 -

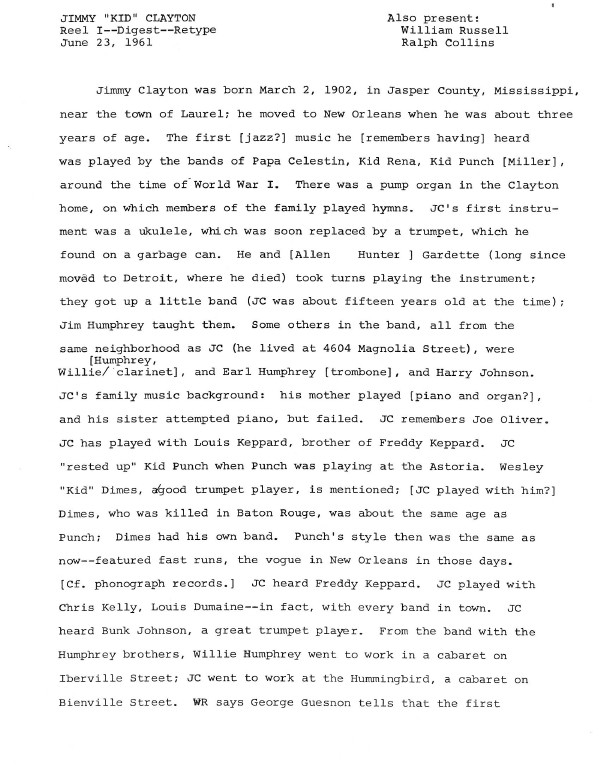

Kid Clayton

June 23, 1961 -

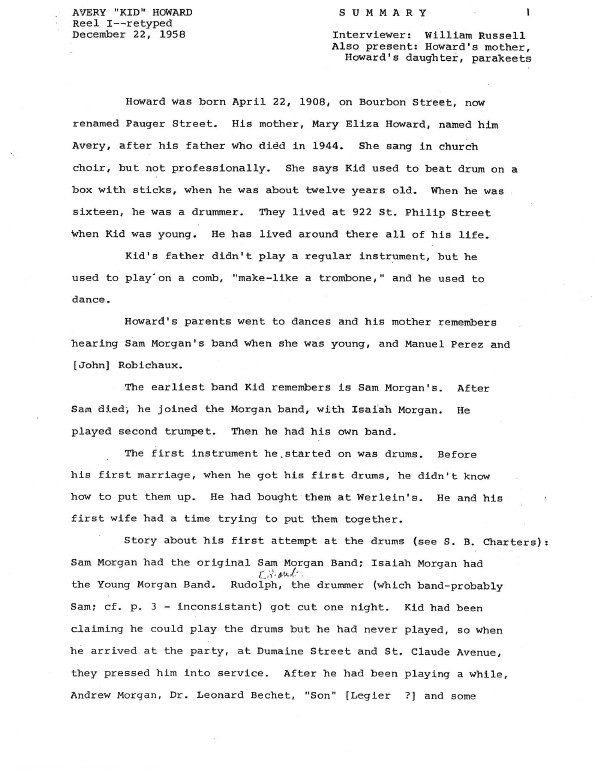

Avery “Kid” Howard

December 22, 1958 -

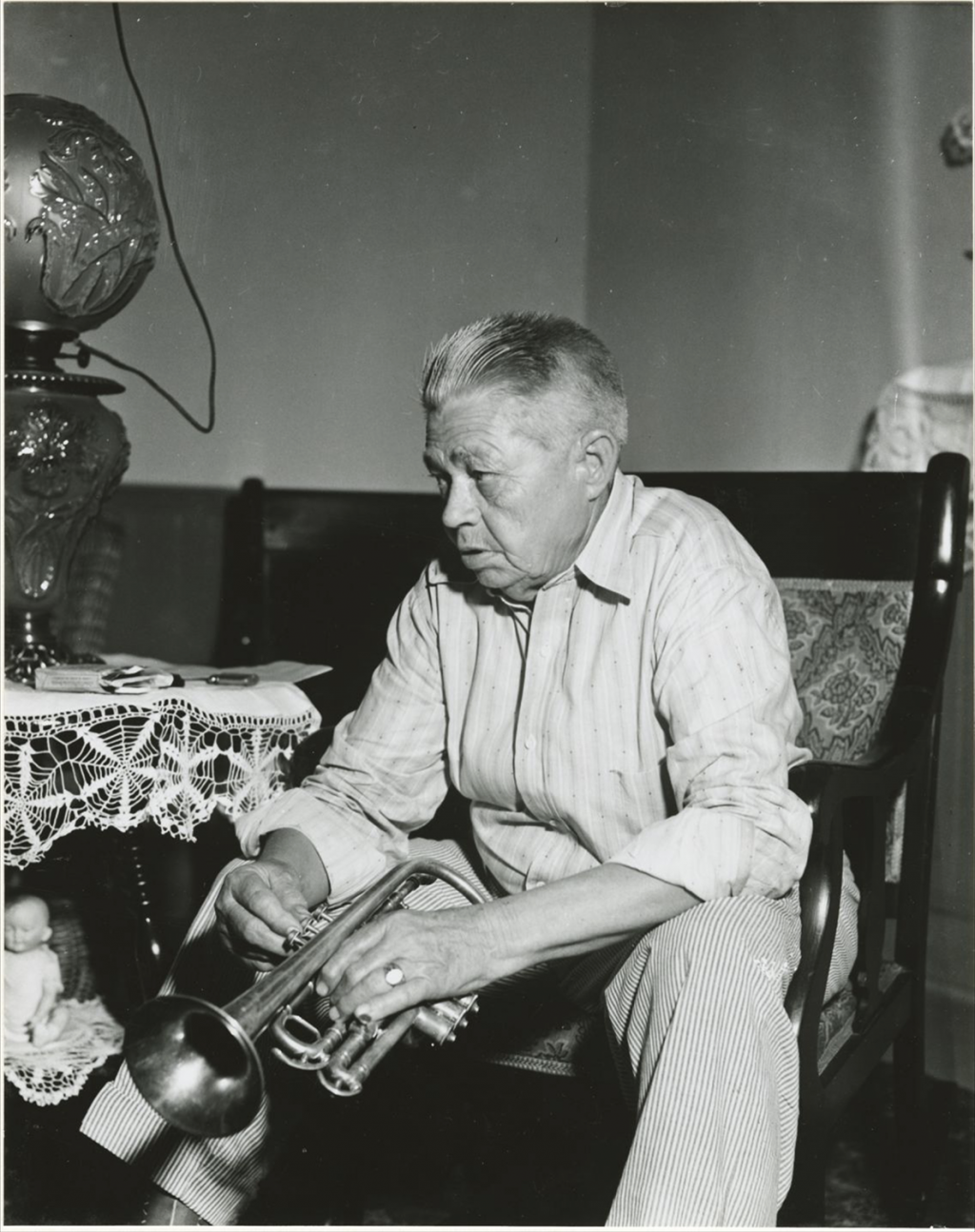

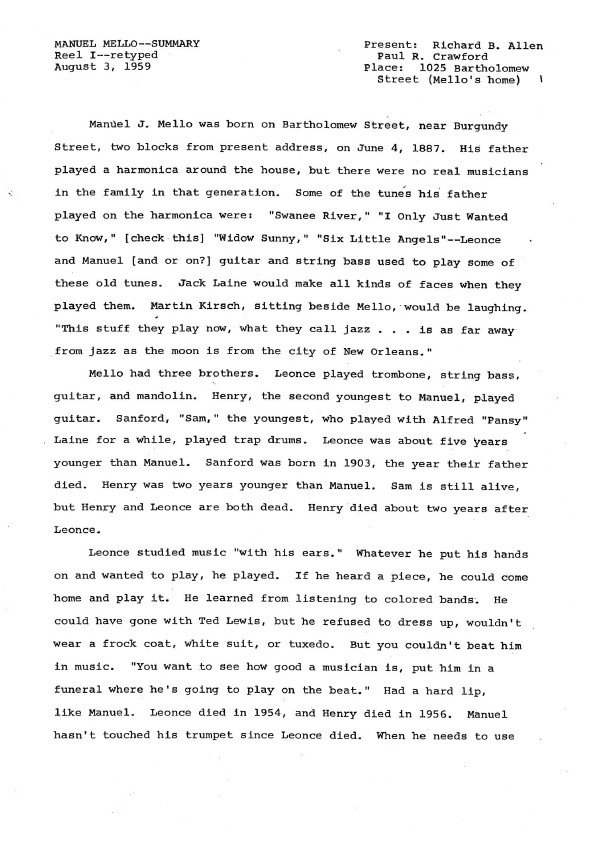

Manuel Mello

August 3, 1959 -

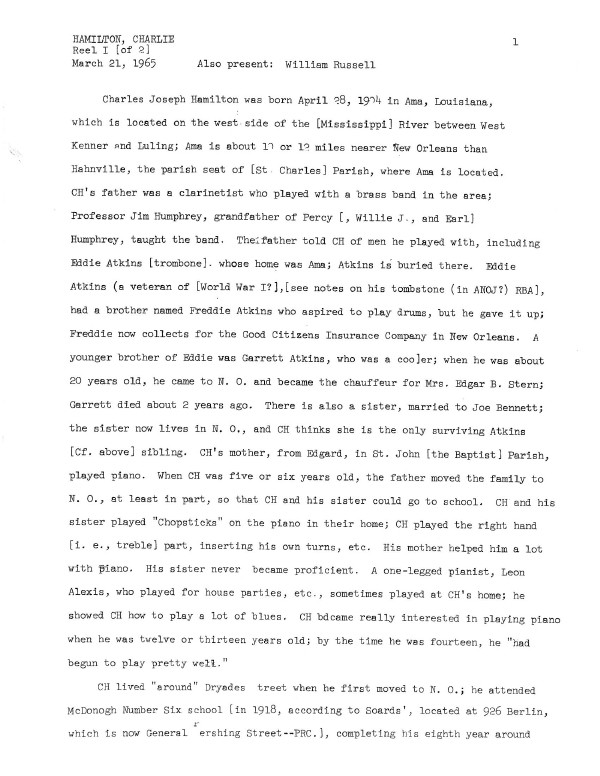

Charlie Hamilton

March 21, 1965 -

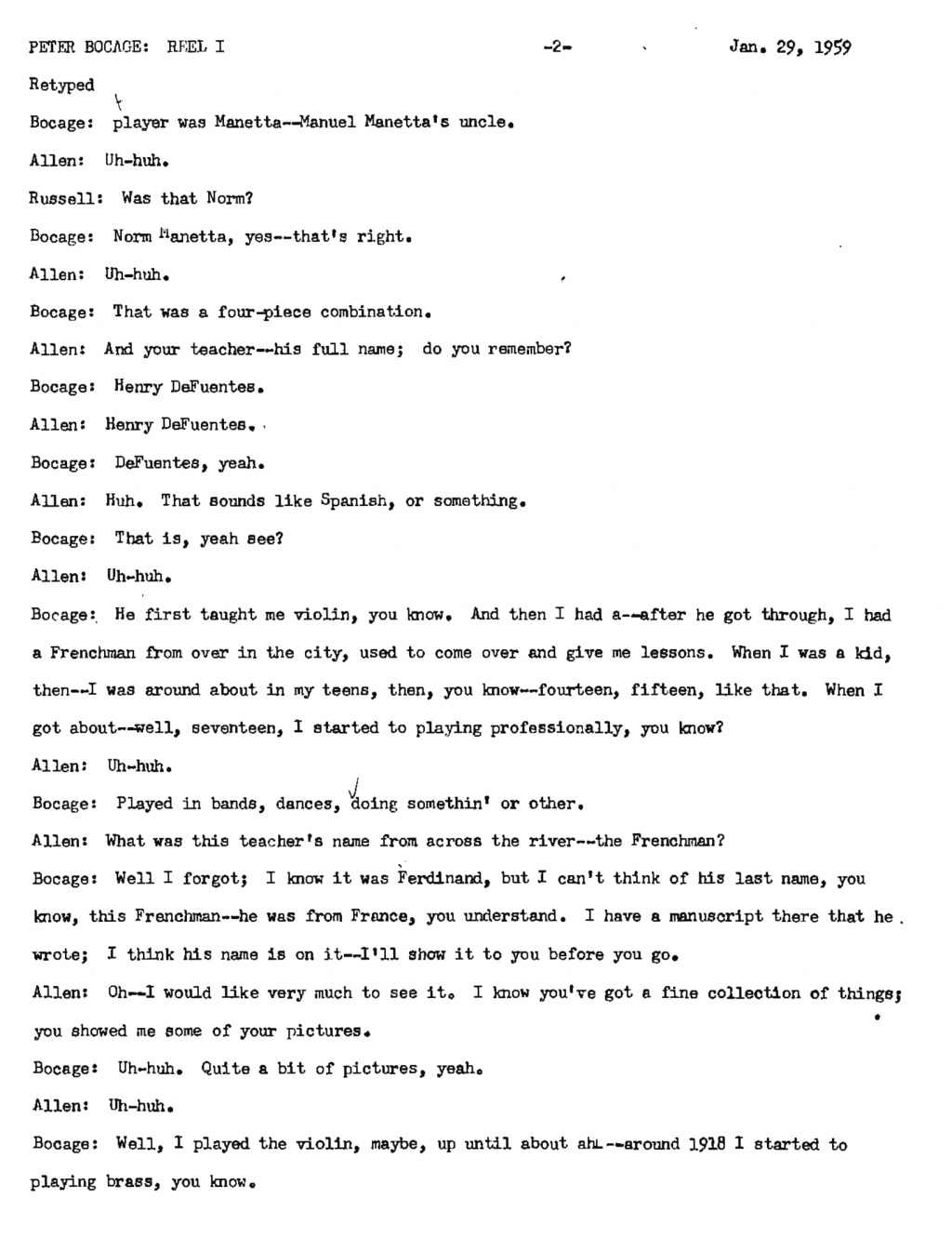

Peter Bocage

January 29, 1959 -

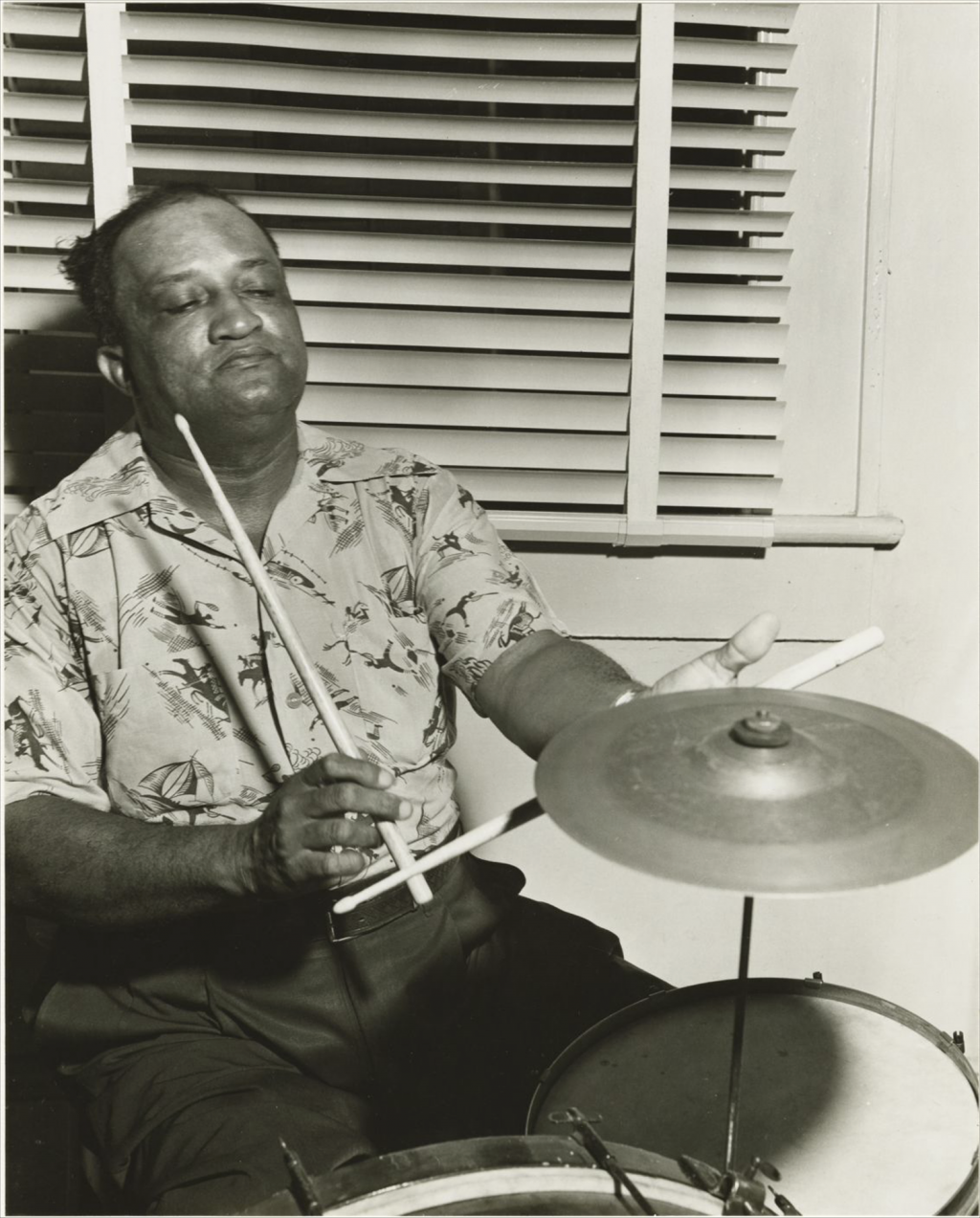

Alex Bigard

April 30, 1960 -

Dolly Adams

April 18, 1962 -

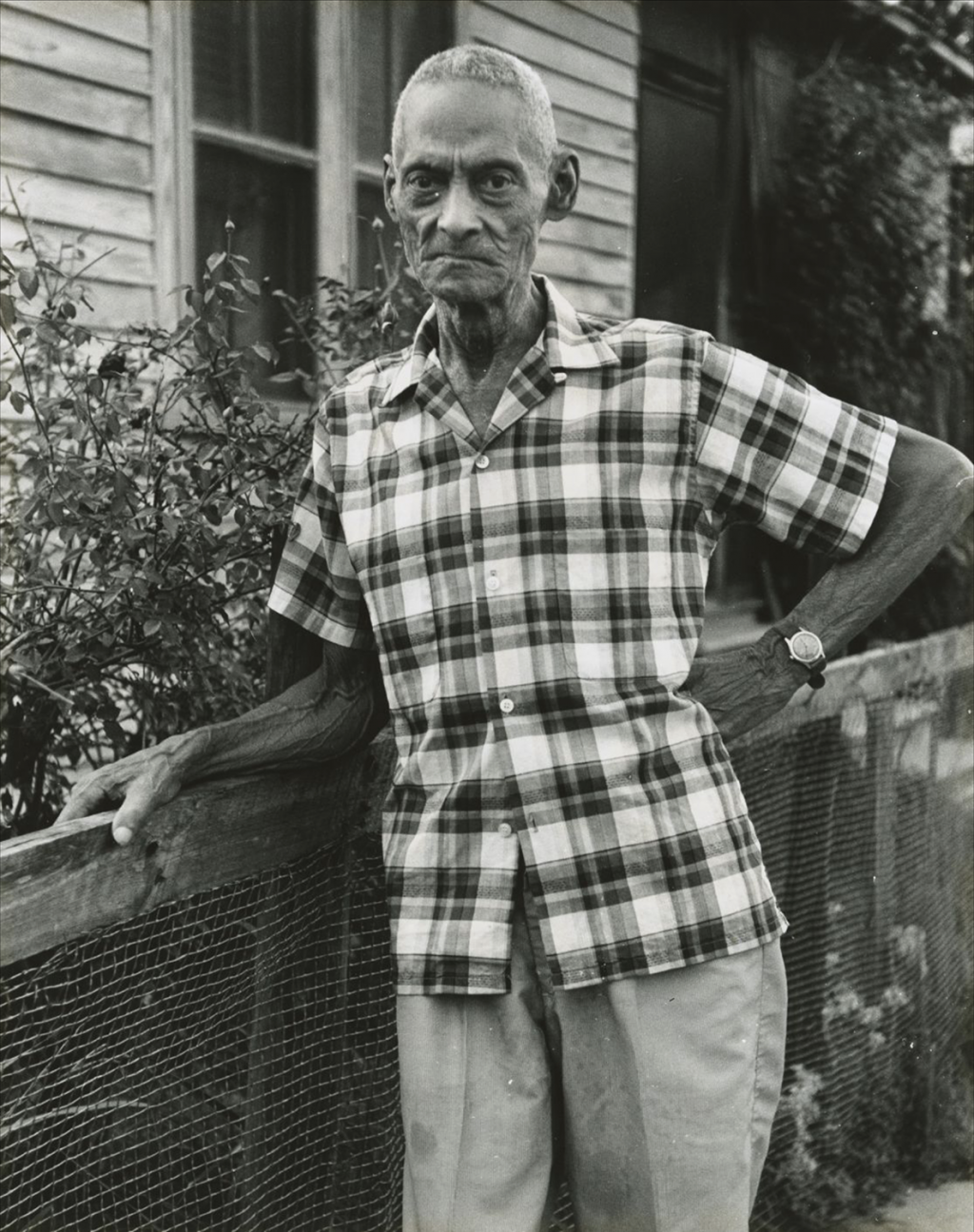

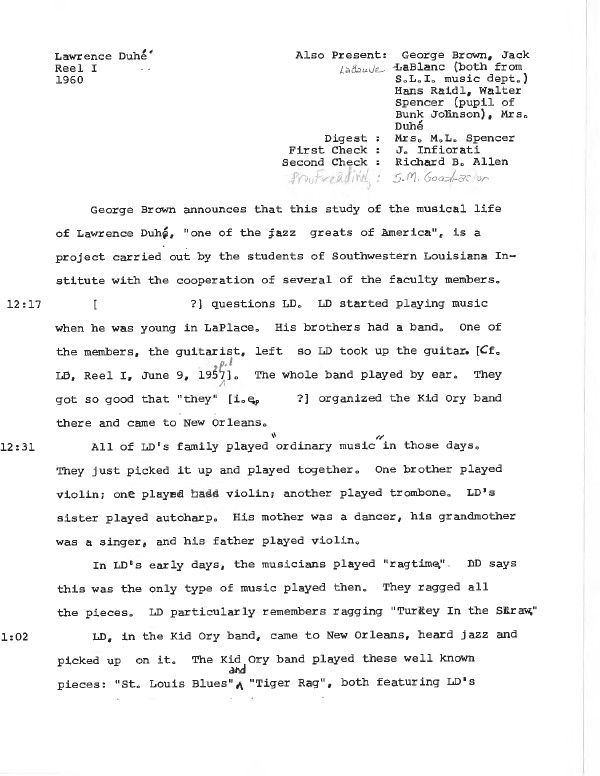

Lawrence Duhé

1960 -

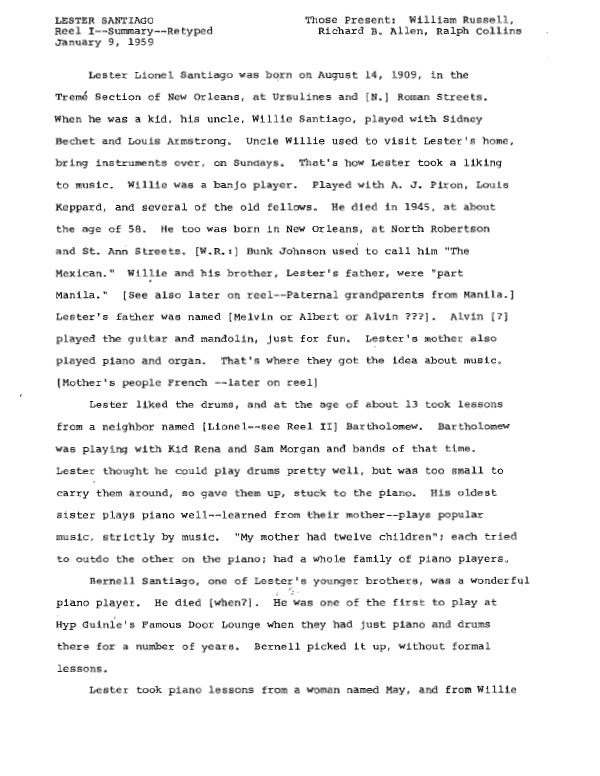

Lester Santiago

January 9, 1959