On 12 October 2016, The Sun’s front-page headline was ‘Here for maternity’. According to its report, splashed over half the page, a National Health Service hospital had been used by nine hundred pregnant ‘health tourists’ in the previous year at a cost to the UK taxpayer of around £4 million in unpaid bills. Officials (unidentified) were quoted as stating that deliveries from non-EU ‘mums’ accounted for a fifth of all births in St George’s Hospital in Tooting, South London. The hospital—read the nation—was being ‘deluged’, an ‘easy target’ for ‘fixers in Nigeria’ who were charging women to use the NHS. The Sun leader, entitled ‘Unhealthy cost’, described the ‘scandal’ as ‘sickening’ (the puns on ‘unhealthy’ and ‘sickening’ presumably intentional), and railed against the £2 billion ‘blown’ on ‘foreign tourists with no right to free NHS care’ each year.

In response to this crisis, the hospital was planning to request ID or proof of asylum from incoming patients in the maternity ward. The article was illustrated with a photo of Bimbo Ayelabola, a Nigerian mother who gave birth to quintuplets by caesarean section at Homerton University Hospital in 2011 at a cost of ‘£200,000’ to the NHS. Despite the nod to ‘fixers in Nigeria’, the image of Ayelabola, holding her five babies, had clearly been chosen to reinforce the age-old stereotype of blacks and the poor reproducing irresponsibly and to excess. Abandoned by her wealthy Nigerian husband, The Sun wrote, she was believed to be still living in the UK with her children, and no doubt claiming benefits, to which, it was implied, she would not be entitled. The subliminal—or not so subliminal—message of the article was therefore: Get this mother out (the paper just about refrained from suggesting that she should be hunted down). The unions may baulk at medics acting as ‘border guards’, the leader commented, but the NHS has an ‘army’ of administrators who need to ‘toughen up’. Apparently, a military response was needed to deal with the scheming dereliction of foreign mothers, who were a threat to the nation’s values and resources alike. In The Sun online (12 October 2016), the article was re-titled ‘Up the Bluff’, as if these women might not even be pregnant.

Why are these mothers so hated? Why are mothers so often held accountable for the ills of the world, the breakdown in the social fabric, the threat to welfare, to the health of the nation—from the funding crisis in the NHS to the influx of foreigners on our shores? Why are mothers seen as the cause of everything that doesn’t work in who we are? We are living in an increasingly fortified world, with walls, concrete and imaginary, being erected across national boundaries, reinforcing the distinctions between peoples. From all sides, in Europe and the US, we are accosted by increasingly shrill voices, telling us that our greatest ethical obligation is to entrench our national and personal borders, to be unfailingly self-regarding and sure of ourselves. It is a perfect atmosphere for picking on mothers, for branding them as uniquely responsible for both securing and jeopardising this impossible future.

The Sun was not alone in this particular brand of vitriol. A few months later, in January 2017, the Daily Mail headlined its front page: ‘One health tourist’s £350,000 bill—and you paid!’ with reference to another Nigerian mother who had come to the UK to give birth on the NHS, this time to twins. Inside its pages the paper reprinted the photo of Ayelabola with her five babies: ‘Haven’t we fallen for this before?’ The figure of £350,000 must have been carefully chosen since it echoes the £350 million that Brexit campaigners had falsely claimed would, on a weekly basis, revert to the UK from Europe straight into the coffers of the NHS (which makes the broken promise somehow these mothers’ fault). The Sun and the Daily Mail are the country’s most right-wing newspapers, but such rhetoric is not without wider effect. According to charity reports from across the UK, hundreds of pregnant foreign women were avoiding antenatal care because they feared being reported to the Home Office or facing costly medical bills. One NHS trust has been sending letters to women with complex asylum claims saying that their maternity care will be cancelled if they fail to bring credit cards to pay fees of more than £5,000. It is also worth noting that, without qualification or apology, The Sun and Daily Mail felt able to issue this onslaught on mothers on the verge, or indeed in the process, of giving birth—the minimal requirement of motherhood, one might say. In this, they are by no means unique. As we will see, tormenting mothers is something of a pastime in the so-called civilised world.

‘Here for maternity’ echoes the title of the 1953 Fred Zinnemann film From Here to Eternity, a phrase which has passed into common parlance in the English-speaking world to evoke a love that will follow its object to the ends of the earth, even if the price is death—the eternity/ maternity echo of the Sun front page suggests that, without drastic action, we are stuck with this problem, with these mothers, for ever. The film is set in the days before Pearl Harbor. Montgomery Clift plays a boxer who refuses to fight with his army mates and prefers to play the bugle, is subjected to cruel treatment by his captain, and is finally killed during the attack. A sergeant (Burt Lancaster) who befriends the Clift character starts an affair with the captain’s wife (Deborah Kerr). The film therefore has all the ingredients for ‘locker talk’ combined with heterosexual passion. But there is a dark side in relation to mothers. In the novel the film is based on, the captain’s wife had a hysterectomy after her unfaithful husband infected her with gonorrhoea. To meet Production Code standards, the film changed this to a miscarriage (there could be no mention of venereal disease). In the film, the husband is still a philanderer, but it is the woman’s own body that has failed her, robbing her of the possibility of motherhood. The fact that male sexual licence during the war might be putting potential mothers at risk could not be spoken. In a film that goes some way to exposing the cult of masculinity in the army, motherhood is an aside, like the irritating drip of a tap. At the opposite end from the Sun article, although drawing on some of the same degraded impulses, mothers in this film slip in and out—mostly out—of focus. This, I will be suggesting, is a pattern. In modern-day Western culture, mothers are almost invariably the object, either of too much attention or not enough.

The Sun’s targeting of foreign mothers came at a time when the image of children without mothers, care or sustenance was at the forefront of the news. Unaccompanied minors were being held in the Calais Jungle, as it came to be known, waiting for the British government to complete the process to allow those who qualify entrance into the UK. In Europe as a whole, there were an estimated 85,000 lone children and young people since the migration crisis began in 2015, roughly one thousand of them in Calais, living ‘feral’ lives: tents housing up to eighteen children or minors, no mattresses, no heating, no blankets. Several of these minors were killed as they made their bid for freedom in the UK—attaching themselves to the underside of trucks, hiding in refrigerated containers or running into the path of cars they often hoped would drive them to Britain. Despite frequent invocations of the Kindertransport that saved German Jewish children from the Nazi genocide by bringing them to England, the process of admitting these children was painfully slow, stalled by the Conservative government at every turn. In February 2017, the government halted its agreement to resettle three thousand child refugees after just 350 had been allowed entry (a figure subsequently revised to 480, although by July 2017 not one unaccompanied child had entered the UK since the start of the year).

The migration crisis of recent years is by no means confined to Europe. But the Calais debacle has special resonance as a monument to inhumanity in our times. Historically, ‘women and children first’ has been accepted practice in moments of high risk. But it is one thing to declare this as a principle, quite another to act on it by letting into the country fragile human beings whose glaring vulnerability will stand as a reminder of the utter nonsense, not to speak of the inhumanity, of pretending that we can save ourselves at the cost of everybody else. ‘The reality, of course,’ commented Bernard Cazeneuve in 2016, when he was French Minister of the Interior, on the breakdown between France and the UK on how to deal with the crisis, ‘is that neither government has chosen to leave people with the right to refugee status in the cold and the mud—women and children least of all.’ The actions of both governments spoke otherwise. Nor did he seem to register the contradiction between calling for a humanitarian gesture on the part of the UK and insisting that, in the longer term, the borders must be made ‘impenetrable’.

Where are the mothers of these children? Behind each and every child there is a story of mothers to be told, but they rarely get a mention. For the most part, they are wiped out of the picture. As if a mother’s loss, which is so often the hidden face and precondition of these children’s fates, is the truly unbearable torment, too glaring a testimony to the cruelty of the modern world, and therefore impossible to contemplate (some of these mothers will have died). One sixteen-year-old boy in the camp, who had fled the war in Sudan, had not spoken to his mother for two years. She did not know if he was dead or alive. A thirteen-year-old simply referred to himself as ‘Mammy’s No. 1’. And after being removed from the Calais camp when it was closed, Samir, seventeen, died of heart failure in January 2017 at the Taizé reception centre in the Saône-et-Loire department of France not long after hearing that his application to join his brother in the UK had been rejected (there have been others—thirty asylum seekers are buried in the Calais graveyard, many in graves without names). His mother could not travel to the funeral. She requested he not be named in full for fear of putting the family in danger from the Sudanese authorities.

These absent, missing mothers are the other face of the pregnant ‘health tourists’ lambasted by The Sun—mothers who are either overlooked completely or are the target of blame, with migration and its miseries being the true story behind both. At the same time, suffering motherhood, a mother bereft of her child, is also a staple of maternal images—Niobe lamenting the murder of her fourteen children, killed by jealous gods; and the Pietà, the Virgin Mary grieving the dead Christ, are two of the most well-known examples. But the mother must be noble and her agony redemptive. With the suffering of the whole world etched on her face, she carries and assuages the burden of human misery on behalf of everyone. What the pain of mothers must never expose is a viciously unjust world in a complete mess.

Using the agony of mothers to deflect from our awareness of human responsibility for the world has a long history. Lamenting mothers have been and often still are the hallmark image for so-called ‘natural’ catastrophes such as earthquakes. In these images, mothers are not, like Bimbo Ayelabola, held responsible. Nevertheless, there is a connection, as their misery is being exploited, shoved in the face of the world, so that others will get off scot-free: contractors who put up buildings that collapse, town planners cutting corners to cram as many people as possible into an inhumanly crowded space. For that reason, Bertolt Brecht objected to the Niobe-like faces plastered over newspaper front pages after the Tokyo–Yokohama earthquake of 1923 that killed an estimated 140,000 people. He praised instead, as the only fully political response, a single newspaper photograph depicting a few solid structures standing among the rubble with the headline: ‘Steel stood’ (only reliably constructed buildings had survived). In earthquakes it is almost invariably the poor who die first, the victims of unscrupulous builders and landlords. And not just in earthquakes, as other disasters have made all too clear: the ongoing tragedy of the hurricanes to have swept the US (New Orleans in August 2005, Haiti in September 2008 and October 2016, Houston in August 2017), and in the UK the Grenfell Tower fire disaster of June 2017. Brecht’s point was that looking at steel structures would not make you weep. It would make you think. And then, hopefully, act, organise, demand redress.

Brecht carried his own political point across into the world of mothers. Perhaps my favourite of his plays on this subject is The Mother (1932)—less known than Mother Courage—in which the mother of the title opposes the war she knows will kill her son. In a key scene, she argues with mothers who are waiting in line to donate their pots and pans for ammunition, in response to a government call announcing it will help to bring the war to an end. She simply points out the obvious—albeit suppressed—fact that their gesture will rather provide the means for the war to continue. This mother is not agonised, even though her son’s life is at stake, but focused, stubborn, articulate. She speaks the truth. Her self-appointed role is to strip deceit from the official dross.

In similar vein, Colm Tóibín’s novella The Testament of Mary (2012) tells the story of the Crucifixion from Mary’s point of view, undoing centuries of glorified maternal pain. Tóibín gives to Mary the last, iconoclastic word in relation to the dead Christ: ‘I can tell you now, when you say that he redeemed the world, I will say that it was not worth it. It was not worth it.’ In the Broadway and London Barbican 2014 production, these are the last lines, spoken by actress Fiona Shaw through her teeth with unerring, barely controlled precision. The Testament of Mary also has Mary flee in horror at the sight of her crucified son, which makes the Pietà image, the mother holding and cherishing the dying Christ’s body—which is meant somehow to make it all okay—a complete lie.

How often are the mothers of lost soldiers and children given voice? How often is the grief of a mother allowed to wander outside the frame of the requisite pathos? Why is it so hard to listen to such a mother, to dignify her with the story she might have to tell? The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina are famous—they started gathering in 1977 to protest the disappearance of their children under the military regime of 1976 to 1983 (in April 2017, they marked the fortieth anniversary of their protest). In the UK, Doreen Lawrence, mother of Stephen Lawrence, murdered on a London street in 1993, has become a campaigner and activist against race crime and also racism in the Metropolitan Police. She has turned the death of her son into a civic task (that in itself was enough to have her and her husband spied on by undercover police). She is a reminder that political agency and the grief of a mother can coexist—a 1998 painting by Chris Ofili depicts her weeping, with the image of her son in every tear. But mothers who expose misfortune as injustice, to use philosopher Judith Shklar’s suggestive formula, by telling the world of the political and social ills behind the death of a child, still struggle to be heard. To put it at its crudest, a mother can suffer, she can be the object of heartfelt empathy, so long as she does not probe or talk too much.

When Gillian Slovo was commissioned by Nicolas Kent to write her verbatim, testimony-based play Another World: Losing our Children to Islamic State, performed at the National Theatre in 2016, she chose to make the voices of three mothers—Samira, Yasmin and Geraldine, each one the mother of a child who had gone to fight against Bashar al-Assad in Syria—her central focus. No mothers in the UK would speak to her; in an atmosphere of strong-arm vigilance and heightened racism against Muslims, they felt that they would place themselves at risk, so she spoke to mothers in Molenbeek in Brussels. (This was after the Paris Charlie Hebdo attack in January 2015, but before Molenbeek became infamous as a centre for terrorists following the Paris Bataclan attack later that year and the subsequent Brussels attacks in March 2016.)

The play dramatises their history, but it is the mothers’ own words that are spoken. These mothers lament the loss of their children: one son dead, one missing and one daughter who chose to remain in Syria after the husband she married in Brussels was killed in combat a matter of weeks after they arrived. They may, as two of them insist, feel they have failed as mothers. But they are also in search of knowledge—it is above all for their failure to know and pre-empt what their children were planning that they castigate themselves. In a world that had become callously indifferent, hostile or meaningless for their children, the mothers are trying to comprehend the choices they made. Two of the mothers, Samira and Geraldine, travel to Syria. Samira goes in search of her daughter Nora—to ‘the end of the earth’, as Samira puts it: ‘wherever you are, I will abandon everything. I will come and get you.’ Geraldine, after the death of her son Anis, travels to the Syrian–Turkish border, where she gives money and clothes that belonged to her son to a pregnant woman, one of the refugees huddled on the border. The pregnant woman says she will call her son Anis. The play ends on this. It therefore seizes the familiar tropes—to the ends of the earth, a mother’s grief—and gives them a new twist, simply by allowing these women to speak: ‘There. That’s the mum’s story,’ is the last line of the play. As if to say, motherhood is part of the polity of nations. Given voice, space and time, motherhood can, and should, be one of the central means through which a historical moment reckons with itself.

Why in modern times is the participation of mothers in political and public life seen as the exception—with the UK appearing to lag behind the rest of Europe, the US and other countries of the world in this regard? Why are mothers not seen as having everything to contribute, by dint of being mothers, to our understanding and ordering of public, political space? Instead, mothers are either being exhorted to return to their instincts and stay at home (on which more later) or to make their stand in the boardroom—to ‘lean in’, to use the ghastly imperative in the title of Sheryl Sandberg’s bestseller—as if being the props of neo-liberalism were the most that mothers can aspire to, the highest form of social belonging and agency they can expect. We are now witnessing what feminist sociologist Angela McRobbie has described as a ‘neo-liberal intensification of mothering’—perfectly turned-out, middle-class, mainly white mothers, with their perfect jobs, perfect husbands and marriages, whose permanent glow of self-satisfaction is intended to make all women who do not conform to that image (because they are poorer or black or their lives are just more humanly complicated) feel like total failures; one of McRobbie’s articles on the topic has the title ‘Notes on the Perfect’. This has the added advantage of letting governments, whose austerity policies always disproportionately target the most vulnerable women and mothers with no chance of ever achieving such an ideal, completely off the hook.

The only good news is that the sheer amount of effort that goes into the stereotype—perhaps into all stereotypes —also bears witness to its vacuity, to the fact that it is hanging by a thread. Mothers, we might say, are the original subversives, never—as feminism has long insisted—what they seem, or are meant to be. The evidence is there, in the many brilliant chronicles I will be discussing later in this book. And yet, despite these testimonies—steadily increasing in voice and volume—the acuity and rage of mothers somehow continue to be one of the best-kept secrets of our times. I have never met a single mother (myself included) who is not far more complex, critical, at odds with the set of clichés she is meant effortlessly to embody, than she is being encouraged—or rather instructed—to think.

A very peculiar form of socially licensed aggression is at play, one that never misses its opportunity. In December 2016, calls went out in the UK to stop mothers involved in separation and child-contact cases—70 per cent of which involve domestic violence—being routinely interrogated by abusive ex-partners in secret hearings in the civil family courts, a practice outlawed in criminal cases. One woman was forced to watch a video of her disclosing sexual abuse while sitting next to the man in question (how this had been allowed to happen was never made clear). More subtly but no less insidiously, when Theresa May was elected prime minister in July 2016 after the Brexit referendum, one minister she retained—in the midst of a reshuffle generally acknowledged as intended to kill off David Cameron’s legacy for ever—was the hugely unpopular Jeremy Hunt at the Department of Health, so he could complete the process of imposing his new contract on junior doctors, after massive protests and strikes. According to his department’s own assessment, the contract is likely to ‘impact disproportionately on women’, notably mothers, due to its unsocial hours. As the Medical Women’s Federation has pointed out, the most affected will be those engaged in part-time training, as well as carers and lone parents (the DH helpfully suggests that those affected should make ‘informal childcare arrangements’). Lawyers have advised that the new contract might be in breach of junior doctors’ right to a family life under the Human Rights Act. ‘Any indirect adverse effect on women,’ the DH report concluded, ‘is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.’

Singlehandedly and carelessly, this new contract will cut off many women’s, notably mothers’, access to the top ranks of the medical profession, making the job of nursing rather than consultancy or surgery their only available path—women as nurses conforming to another stereotype. One newspaper report on the dispute had the title ‘The new junior doctors’ contract is blatantly sexist—so why doesn’t Jeremy Hunt care?’ Caring might be the problem—permitted on condition that it is hived off into a type of gender-specific, low-grade, women-only quarantine. As if a dedicated neo-liberal society can acknowledge the role of women as carers, but only so far, and certainly not if it disrupts any of the other arrangements by which it believes it can most efficiently perpetuate itself. All this takes place with blithe disregard for the indispensable role of mothers in securing any future whatsoever (motherhood as the downside of the modern world).

In July 2015, a report issued by the Equality and Human Rights Commission stated that every year in the UK a staggering 54,000 women lose their jobs as a result of their pregnancy. Seventy-seven per cent of women and new mothers in work experience some form of negative treatment (bullying, snide remarks, straight insults, the suggestion that they are a burden on their employers and the state). Overall, the vast majority of pregnant women face unlawful discrimination or adverse experiences each year (77 per cent of pregnant women and new mothers face discrimination in the workplace compared with 45 per cent a decade ago). Under present law, they have three months to file a case (an impossibility for most women reluctant to do so during their pregnancy). The problem seems to be getting considerably worse—those estimated 54,000 women fired are double the number reported in 2005. In 2016, Citizens Advice reported a 25 per cent increase over the previous year in people seeking advice on pregnancy and maternity issues. Maternity Action is demanding that the legal protection for pregnant women provided by the Maternity and Parental Leave Regulations (Regulation 10) be extended to include the period of notification of a pregnancy to six months after returning to work, the time when women are most vulnerable.

‘The government’s approach,’ commented Maria Miller, chair of the 2016 parliamentary report on workplace discrimination, ‘lacks urgency and bite’ (promising a review of the situation, the report rejected the demand for a German-style ban on employers making women redundant during and after pregnancy other than in exceptional circumstances). For women at the recruitment stage, there is no redress—if you are visibly pregnant at interview, you are very unlikely to get the job. Likewise, in the US, women are meant to be legally protected against discrimination, but they are not. Between 1935 and 1968, the principle was written into federal policy that women with children were unemployable. The situation has barely improved. One woman, working for Procter & Gamble’s Dolce & Gabbana cosmetics shop at Saks Fifth Avenue in 2014, was told, when she mentioned that one day she would like to be a mother: ‘Pregnancy is not part of the uniform.’ In February 2015, at four months pregnant, after needing first to sit down at moments during her shift, and then short respite periods built into her day—agreed by the management—she was fired.

The law needs to be changed, but the problem goes deeper. A friend of mine with a baby under a year old was about to return to work, hoping to conceive her second child in the coming year. She fretted that this would be seen as abusing the system of legally stipulated maternity leave. The idea that everyone in her office, indeed everyone full stop, relies on women having babies—witness the instant social panic at any hint of a falling birth rate—or that she should feel free to plan her pregnancies in the way that felt right for her and her family, did not occur to her (personally, I was just impressed that she didn’t seem fazed by the prospect of two babies under the age of two). Nor was she aware that, were she not in a job with such legal guarantees written into her contract, she would most likely be sacked. She felt guilty. Struggling not to allow motherhood to take over her life completely, she had nonetheless bought into the belief that it was something everyone, apart from her and her baby, should be protected from, something that should not interfere with anything or anybody else.

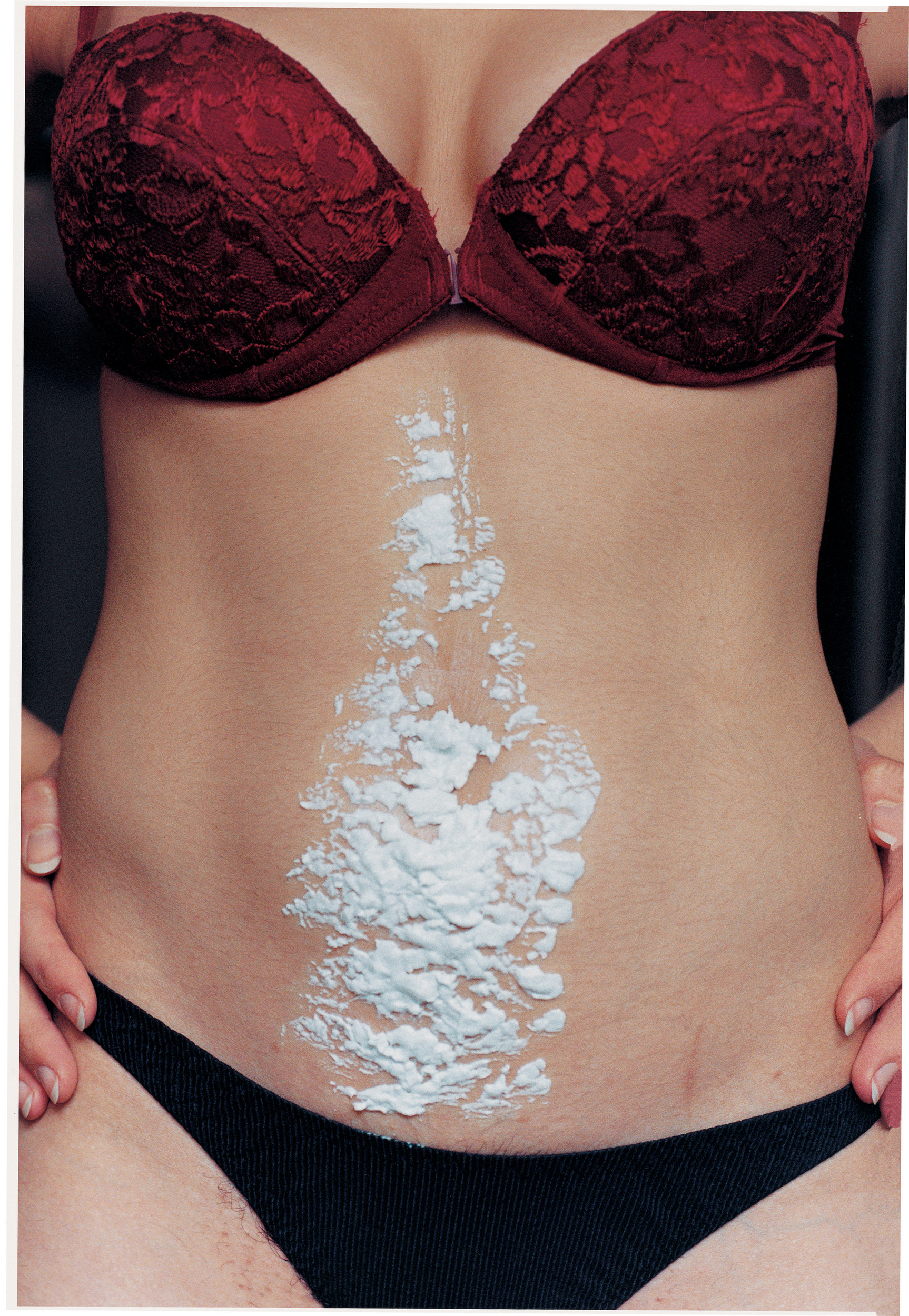

No less shocking—in some ways more so—nearly half (41 per cent) of all pregnant women in the UK face risks to their health and safety at work. Four per cent of pregnant women and new mothers in the workplace—a figure Maternity Action calls ‘astounding’—resign from their jobs because of health and safety concerns. The existing obligation on all employers to carry out a risk assessment that considers female employees is, they state, ‘woefully inadequate’. Legally, if an employer refuses, or is unable, to make the working environment safe for these women then they are entitled to be suspended on full pay. It doesn’t happen. Maternity Action is demanding that a ‘no safe work’ leave be legally formalised. Instead, women in such conditions are forced to take early maternity or sick leave, sign themselves off, as if, once again, it were their own bodies and health at fault.

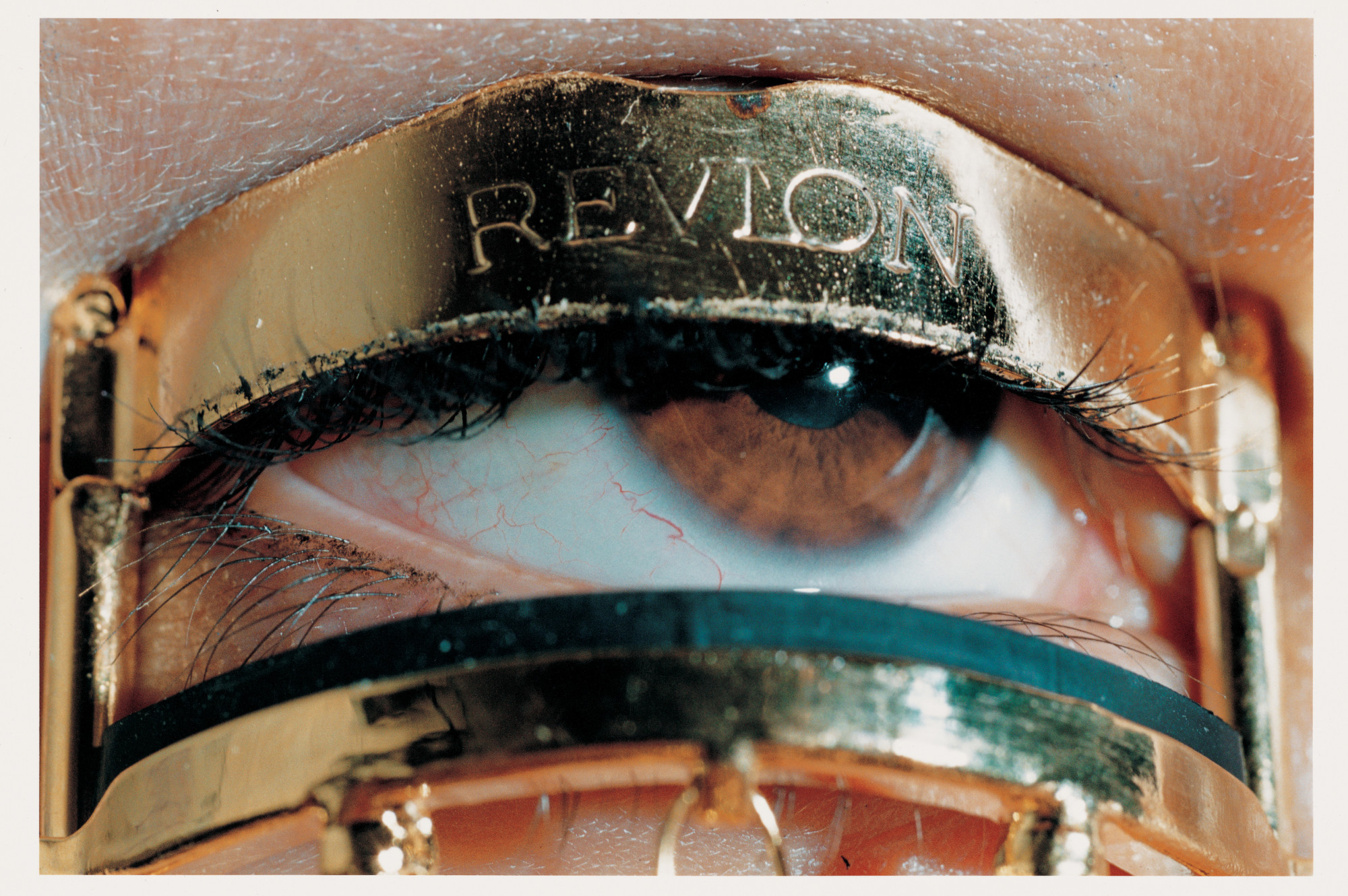

As feminism has long pointed out, most bodily experiences of women from menstruation to pregnancy to menopause without distinction tend to be regarded as a form of debilitation or illness: too much blood and guts, bodies either too wet or too dry, bodies that inconveniently blur the boundaries between inside and out. Punishing pregnant women and mothers is part of a pattern (British maternity pay is among the worst in Europe, behind, for example, Croatia, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, Spain and France). Although we should never underestimate the effects of an increasingly ruthless, profit-driven global economy, it seems that in all these cases there is something far more than a cost–benefit analysis involved. The same employers who provide routine assessments for workers with a health condition, an injury or disability are still refusing individual risk assessments for pregnant women and new mothers. To add insult to injury, 10 per cent of pregnant women in the UK are discouraged by their employers from attending antenatal clinics, putting their health and that of the unborn baby at risk.

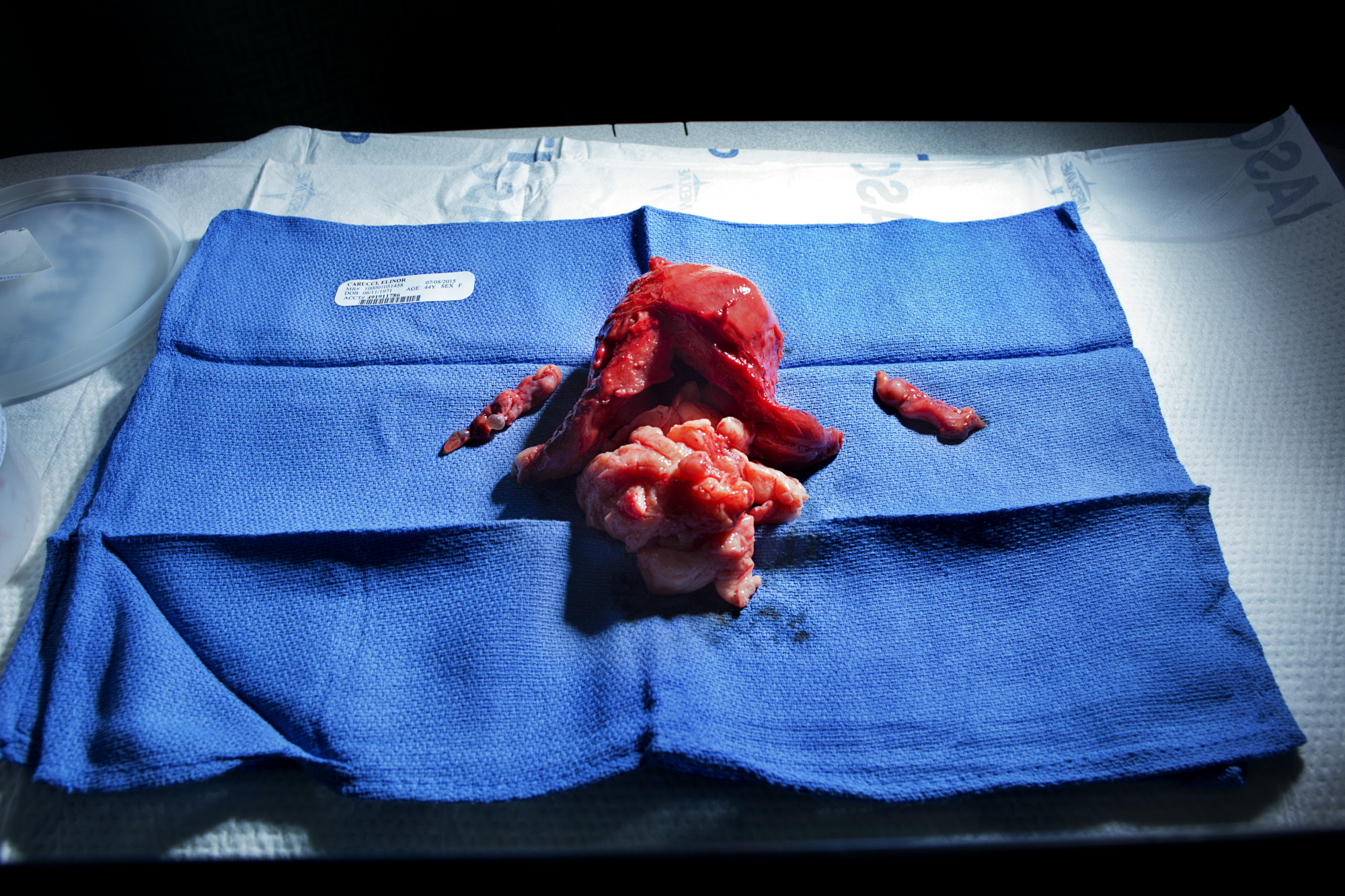

So if I had been more honest with my friend, I would not just have pointed out that everyone needs mothers, or at least some women to be mothers, and that being a mother is hardly an antisocial activity. I would have added that, while this much is undoubtedly true, and a banal fact of life, we should never underestimate the sadism that mothers can provoke. I probably would have been somewhat apologetic (as if merely having such an ugly thought made me personally responsible for this sorry state of affairs). The reasons for this are many, as we will see, but one reason why motherhood is often so disconcerting seems to be its uneasy proximity to death. First, in the risks of childbearing, which vary so dramatically across race and class: in the US, non-Hispanic black, American Indian, Alaska Native and Puerto Rican women have the highest infant-mortality rates, the disparity between non-Hispanic blacks and whites having more than doubled over the past decade; in the UK, 66 per cent of the female prison population are mothers, and twice as many black women are incarcerated than white for the same offences, while asylum seekers and refugees account for 14 per cent of all maternal deaths (despite comprising only 0.5 per cent of the population). But also in the sense, less tangible but no less powerful, that the fact of being born can act as an uncanny reminder that once upon a time you were not here, and one day you will be no more. ‘We have a winding sheet in our Mother’s womb, which grows with us from our conception,’ John Donne wrote, ‘and we come into the world, wound up in that winding sheet, for we come to seek a grave.’ More simply, being born—each time testimony to the monumental physical and mental strength of all mothers—also alerts us to the irreducible frailty of life. Mothers require protection, solace and support from the first moment they find themselves the bearers of new life. Instead, you would think that mothers were the danger against which the workplace needs to protect itself.

The figures speak for themselves. Employers do not want pregnant women and new mothers on the premises, or if they do, they do not want them healthy and safe, nor for them to attend the clinics that will protect their well-being and the lives of their unborn babies. ‘If Americans Love Moms,’ the New York Times headlined a recent article by Nicholas Kristoff, ‘Why Do We Let Them Die?’ He is reporting on the fact that the US mortality rate for mothers in pregnancy or childbirth is higher than in any other country in the industrialised world: ‘We love mothers or at least we say we do. We are lying.’ The message, spoken and unspoken, is clear: we will not take care of you, or allow you to take care of yourself, because part of us wants you out of here, or dead. The visceral fact of motherhood, the fons et origo of our being in the world, is an affront to normal—meaning, free of mothers and babies—life. There is a crucial feminist point to be made here. The problem for everyone, but especially men, Adrienne Rich writes in her path-breaking Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976), is that ‘all human life on the planet is born of woman’ (the first line of her book). ‘There is much to suggest,’ she continues, ‘that the male mind has always been haunted by the force of the idea of dependence on a woman for life itself.’

The subject of mothers is thick with idealisations, which have been among the foremost targets of feminist critique (ideals are one of the surest ways of punishing others as well as oneself). ‘Stop peddling the myth of the perfect mother’ has been the recent plaint of the founder of Netmums, one of the biggest UK parenting websites, set up in 2000. It is one of the most striking characteristics of discourse on mothering that the idealisation does not let up as the reality of the world makes the ideal harder for mothers to meet. If anything, it seems to intensify. This is not quite the same as saying that mothers are always to blame, although the two propositions are surely linked. As austerity and inequality increase across the globe, more and more children are falling into poverty, more and more families are fighting a rearguard action to protect their children from inexorable social decline. Social unrest is therefore likely to increase. In this context, as in so many moments of crisis, focus on mothers is a sure-fire diversionary tactic, not least because it so effectively deflects what might be far more disruptive forms of social critique. Mothers always fail. It will be central to my argument that such failure should not be viewed as catastrophic but as normal, that failure should be seen as part of the task. But because mothers are seen as our point of entry into the world, there is nothing easier than to make social deterioration look like something that it is the sacred duty of mothers to prevent—a type of socially upgraded version of the tendency in modern families to blame mothers for everything. This neatly makes mothers guilty, not just for the ills of the world, but also for the rage that the unavoidable disappointments of an individual life cannot help but provoke.

Hunt’s new doctors’ contract is by no means the first time lone mothers have been targeted for especially vindictive treatment. One of the earliest proposed measures of Tony Blair’s 1997 government was to cut benefits to single mothers. This so went against the supposed humanitarian ethos of New Labour that he immediately had to back down. But his move was symptomatic of the way single mothers have often borne the brunt of a particular form of punitive social attention. In troubled times, the most vulnerable always tend to be the easiest targets of hatred. But might there also be a connection between the demand for singular devotion so regularly directed at mothers and the hostility that single mothers—who, even if not by choice, could be said to be obeying this injunction to the letter—have historically provoked? As if the single mother brings too close to the surface the utter craziness, not to say the unmanageable nature, of the idea that a mother should exist for her child and nothing else.

A single mother also stands as a glaring rebuke to the family ideal. In the US, the number of single mothers has nearly doubled over the past fifty years. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the number of lone, including unmarried, mothers in the UK rose faster than at any other time in history, seemingly unaffected by an increasingly strident Conservative rhetoric of blame. The most pervasive image was of an unemployed teenager who had deliberately got herself pregnant to claim benefits, although as Pat Thane and Tanya Evans point out in their 2012 study of twentieth-century unmarried motherhood, she was ‘very rarely to be found’. Over the past century, single mothers have variously received the epithets of ‘sinners, scroungers, saints’ (the title of Thane and Evans’s book). The first and last string them between religious opprobrium and holiness (neither of this world), the second more prosaically casts them as objects of moral contempt. Although today the religious vocabulary is somewhat muted, by depicting Bimbo Ayelabola in the unmistakeable guise of a welfare ‘leech’, the Sun headline was therefore following a tradition (‘saint’ is hardly an epithet about to be applied to foreigners).

Long before the migration crisis provided its image of the alien, invading mother, the single mother, it seems, was the original ‘scrounger’, the term that allows a cruelly unequal society to turn its back on those it has itself thrown to the bottom of the social scrapheap. This manipulative, undeserving mother was the perfect embodiment of the so-called ‘dependency’ culture, an idea that is being revived today in the UK in order to justify an even more full-scale dismantling of the welfare state, and more widely in the global North as part of austerity measures that target social provision above all else. ‘In a country where many children do without homes and food,’ Michelle Harrison writes in a report issued in Canada by the Metis Women of Manitoba, ‘it is easier to punish one pregnant woman than to alleviate the condition of many.’

Again, it is also worth noticing how far the real vulnerability and needs of a single mother, not to speak of those of the child or children for whom she has responsibility, seem to work in her disfavour. Lone parents, especially unmarried mothers, are still one of the poorest groups in Britain; it is estimated that they will lose 18 per cent in the universal credit squeeze. According to a 2013 US census, single mothers earn an average income of $24,000 compared with the $80,000 earned by married couples with children. As if genuine neediness—being, or having once been, the baby of a mother—is what Conservative rhetoric hates most. Perhaps when right-wing politicians screw up their noses at scroungers, asylum seekers and refugees, it is their own vaguely remembered years of utter dependency that they are trying, and instructing us, to repudiate. The one who most loudly promotes the ideal of ironclad self-sufficiency must surely have the echo of the baby in the nursery hovering somewhere at the back of his or her—mostly his—head.

We should also remember that it was not until 1973 in the UK that, following divorce or separation, mothers gained equal custody rights over their children. The father was legally the sole parent and a mother was only granted custody of her children until the age of seven. Up until the 1920s a woman was only free to apply to the courts for equal custodianship if she was legally married. A single woman was robbed of her children, tarred with deficiency, as if she herself were the reason for the economic constraints and social exclusion from which she was likely to suffer. In fact, the prejudice was no respecter of class. The nineteenth-century aristocrat Caroline Norton was denied all access to her three sons when she finally left her physically abusive and profligate husband (he subsequently failed to tell her when one of them suffered a fatal accident).

Historically, single mothers are not the exception. Throughout the twentieth century the number of single mothers in the UK was high, matched by the levels of illegitimacy precipitated by both the First and the Second World Wars (during the wars, with so many men at the front, single motherhood was something of a norm). The perfect family model of a married heterosexual couple, against which single mothers are so harshly measured, is an anomaly, a mere blip of the statistics, typical only between 1945 and 1970. When Pat Thane laid this out in 2010 in ‘Happy Families? History and Family Policy’, the question mark of the title was the giveaway and provocation. Her pamphlet provoked an outcry from Conservatives and family lobbyists determined to prove the lasting damage inflicted on children by family breakdown and the unconventional child-rearing arrangements that have been its consequence (I am inclined to think that the real scandal might have been the idea that a single mother, however hard her life, might also be happy). Although absentee fathers are also indicted, the barely hidden subtext of this rhetoric is that single mothers cannot be entrusted with the care of their own children. In the UK, the number of young women who had their children forcibly removed for adoption over three decades from the 1950s to the 1970s is only today coming to light (in October 2016, the Catholic Church issued an open apology leading to calls for a public inquiry). The irony is glaring. Mothers in the home are expected to manage more or less on their own—one of feminism’s loudest, most persistent and fairest complaints—but the one thing a mother cannot possibly manage by herself is mothering.

It is, of course, a predominantly white, middle-class domestic ideal that is being promoted, one which fewer and fewer families can possibly live up to. But that has not prevented it from spreading down the class spectrum and across all ethnic groups, trampling over the ‘motherwork’ of women of colour, which, as Patricia Hill Collins, scholar of African American studies, was the first of many to insist, cuts across private and public, and is not corralled inside the family unit. Instead such work plays a crucial role in collective, community survival in a racially discriminating world, thereby unsettling just about every white-dominated dichotomy on the subject of mothers. Today the relationship between white mothers and mothers of colour is repeating an age-old history, especially in the US, as undocumented migrants take care of the children of white middle-class mothers, relieving them of the burden of childcare so they can parade the seamless compatibility of their professional and domestic lives.

When Zoë Baird, nominated for attorney general in 1993, was found to be employing two undocumented Peruvian immigrants, one as a babysitter, there was a public uproar for her violation of immigration law prohibiting the hiring of illegal aliens. The practice, it turned out, was widespread, though no one, least of all the hiring mothers, wanted to talk about it. Notably absent in the outcry over the case of Baird, who had to step down as potential attorney general, was the slightest concern for the migrant mothers themselves. Their working conditions are often inhuman. Maria de Jesus Ramos Hernandez left her three children in Mexico to work for a household in California, where she was repeatedly raped by her employer, who threatened her with jail as an illegal migrant if she did not submit. Her case received little attention, but the story is typical. These migrant women, who so often have to leave their own children behind, are mostly paid a pittance. Once again lost motherhood is the tale behind other forms of exploitation. Like Bimbo Ayelabola, they are accused of leeching off the welfare system (a charge previously targeted at job-stealing migrant men). In fact, they are being used as a cheap labour force that greases the economy while allowing other mothers to get rich. Solidarity among mothers, across class and ethnic boundaries, is not something Western cultures seem in any hurry to promote.

It is, therefore, immensely reassuring to register the instances of women organising against the forms of prejudice and social exclusion directed towards those mothers who have tried, and are still trying, against the harshest material odds, to create a viable life for themselves. In 1918, the pioneering National Council for the Unmarried Mother and her Child was set up in the UK to support such women, and is still active today (renamed the National Council for One Parent Families in 1970; since 2009 as Gingerbread, with which it merged in 2007). Its history includes moments of unlikely solidarity. During the First World War, the Prince of Wales Fund decided not to support unmarried mothers. One of their midwives told the executive committee about a ‘respectable married woman’ she had attended the previous day who had said she was happy to ‘wash herself and leave her child unwashed’ so that the midwife could go to plead the cause of unmarried mothers.

A report on mother and baby hostels set up during the Second World War—another moment when unmarried mothers were the target of moral panic—describes how the matrons turned desolate premises into havens for ‘utterly friendless girls’ who may never before have known a home or ‘whose parents set their own petty respectability above the ordinary decencies of human relationships’. The girls would leave the hostels ‘with a great deal more confidence than when they arrived’. The report was never published.

Note, too, the sexual undertow (these girls are not ‘respectable’). One of the greatest wartime fears was that single girls would become pregnant by black American servicemen, with dire consequences for the race of the nation and potentially for the servicemen themselves. ‘Any English girl who walks out, however harmlessly, with a coloured American soldier,’ a lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary, the Queen Mother, wrote to Violet Markham in 1942, ‘should be made to understand that she will very probably cause his death.’ In the same breath her remark manages to express solicitude for the girl and the soldier, and raw prejudice against the idea of ‘mixed marriages’ and their potential offspring.

During the First World War, Markham had been secretary to an official investigation into suggested ‘immorality’ among servicewomen stationed in France. The charge was common. Gail Lewis, sociologist and writer on race and gender, was born to a white mother and a black father. In a conversation written as an open letter to her mother, Lewis quotes Major-General Arthur Arnold Bullick Dowler, who in 1942 wrote a secret missive, ‘Notes on Relations with Coloured Troops’: ‘White women should not associate with coloured men. It follows then, that they should not walk out, dance, or drink with them. Do not think such action hard or unsociable. They do not expect your companionship and such relations would in the end only result in strife’ (the letter was published in the first volume of Studies in the Maternal, one of the most open-minded online journals on the complexity of mothering). The fallout from these attitudes would track Lewis for the rest of her life. ‘How others cast you’, she addresses her mother, ‘as sexually depraved and morally bankrupt.’ A white mother bearing a black child surpassed all understanding.

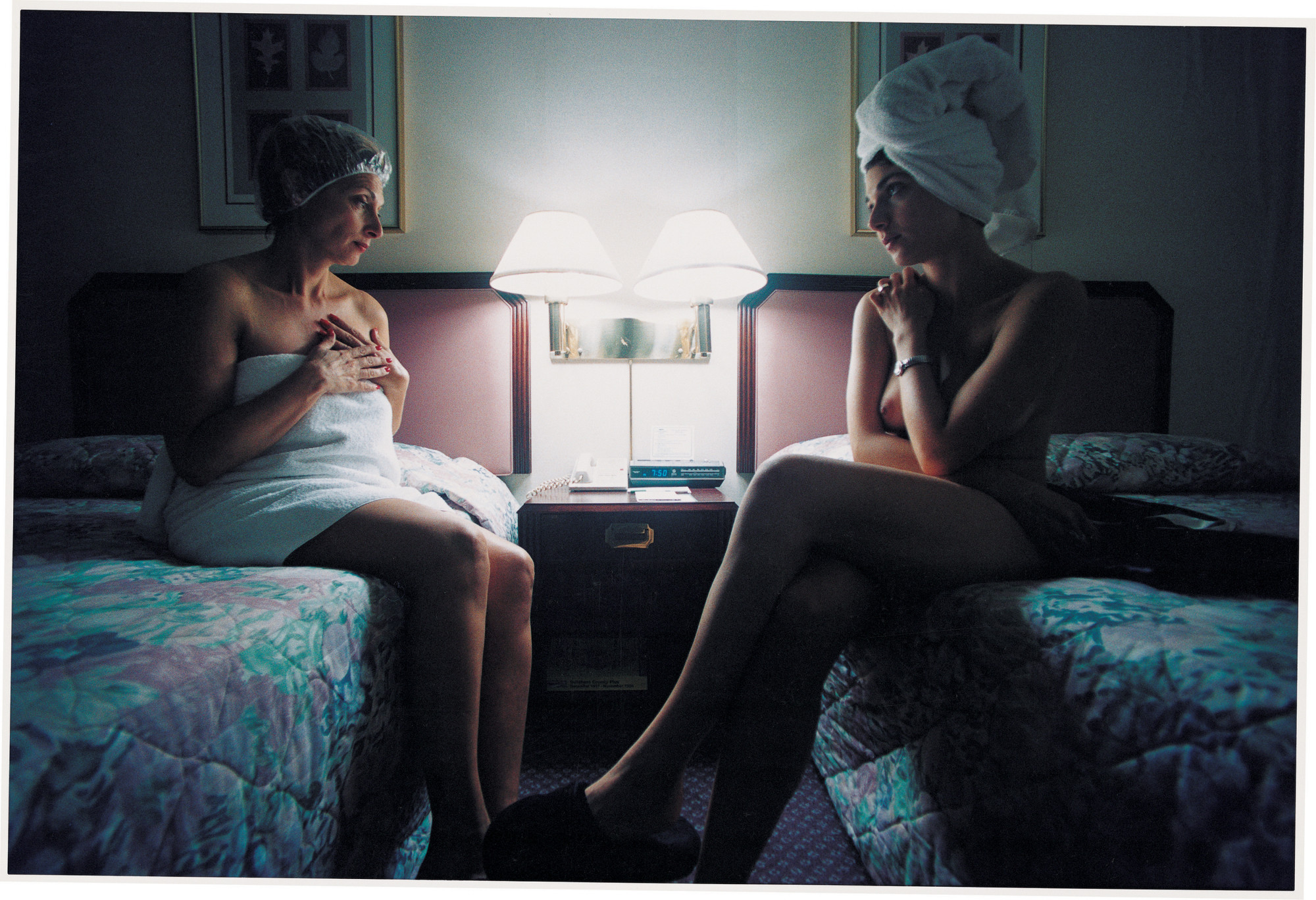

As so often in relation to mothers, something about sexuality—its pleasures and dangers—is at play (this too will be my refrain). It is another common assumption that a single mother is a woman who puts her sexual life ahead of her social responsibility. She therefore has only herself, or rather her voracious sexual appetites, to blame. Manipulative or sexual, the single mother exhibits either too much control over her sexual life or not enough—what is hardly ever mentioned in relation to teenage pregnancies is the possibility of child abuse and rape. Behind the idea of maternal virtue, therefore, another demand and/or reproach. A mother is a woman whose sexual being must be invisible. She must save the world from her desire—thereby allowing the world to conceal the unmanageable nature of all human sexuality, and its own voraciousness, from itself (as if sexuality never exists outside the bounds of married life).

Even in the years leading up to the 1960s, when there was more sympathy for the predicament of single mothers, the basic assumption was there. ‘Innocent’ girls could get into trouble and merited understanding provided, in the words of Thane and Evans in the opening pages of their book, ‘they did not flaunt their transgressions.’ Nor is the childless woman immune from sexual taint. ‘Surely,’ as one journalist summed up a common presumption about the declining birth rate in twenty-first century France, ‘a woman who refuses to be a mother enjoys lovemaking rather too much?’ The shudder of disapproval barely conceals its own excitement. At whatever point of the spectrum—no babies or illegitimate babies or too many babies—women find themselves caught in a steel vice (the most recent version being the charge that excessively reproducing mothers are responsible for climate change).

I started this chapter by asking: what are mothers being asked to carry, what forms of failure and injustice are they made accountable for, above all, in the modern Western world? What are the fears we lay on mothers, both as accusation and demand (the one following the other)? Why do we expect mothers to subdue the very fears we ourselves have laid at their door? For much of the rest of this book, in dialogue with some of the most searching writing on mothers, I will be attempting some kind of answer. In the meantime, since the most powerful ideologies of motherhood present themselves as eternal and unchanging—from here to maternity—the question must be: has it always been thus? After all, it is one of the first principles of feminism that, if you want to challenge a stereotype, especially one masquerading as nature or virtue or essence, if your aim is to drag it down from its pedestal or yank it up from the dirt where it festers, then try and find where it all started. Better still, look to a place and time when—maybe—it was not even there.

“Now” was originally published in Jacqueline Rose’s Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2018. Republished here with permission from the publisher.